POCUS for HRS

The last few weeks have been a sort of fever dream - I’ve been working a lot, had to plan/organize/deliver our internal medicine intern POCUS training during orientation, and I adopted a second dog. The dog has been a lot haha. And it’s made that other stuff quite a bit harder. But look at him!

Velez JCQ, Petkovich B, Karakala N, Huggins JT. Point-of-Care Echocardiography Unveils Misclassification of Acute Kidney Injury as Hepatorenal Syndrome. Am J Nephrol. 2019;50(3):204-211. doi:10.1159/000501299

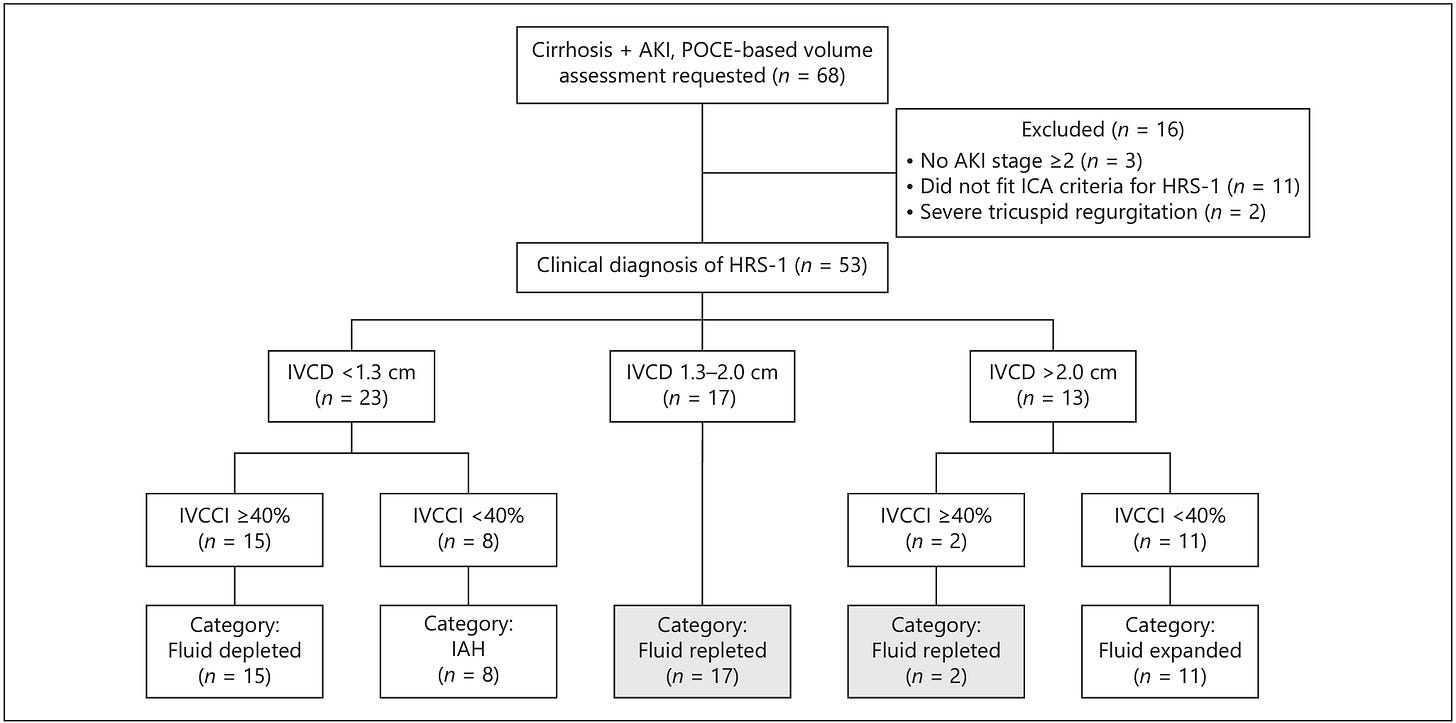

This was a cool paper from a few years back I found out about in this brief paper outlining a similar pilot study. The researchers cite literature indicating that we get the diagnosis of hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) incorrect 30-60% of the time. Part of the diagnostic criteria is failure to improve with 48 hours of colloid volume expansion (1 g/kg/d albumin up to max 100 g/day) and the authors argue that this criteria is applied to broadly such that some patients are iatrogenically volume overload, others are under-resuscitated, and some suffering from intra-abdominal hypertension go unrecognized and untapped. To address this, researchers formed a POCUS team that could be consulted for volume assessment in cirrhotics with presumed HRS. They performed several cardiac views but the lone info they used to make suggestions to managing providers was the IVC diameter and collapsibility index. They excluded patients with unknown baseline creatinine, severe valvular disease, any indication for intensive care, and pre-existing CKD 4 or 5. In the decision tree below you can see they used IVC diameter cutoffs of 1.3 cm and 2 cm and a collapsibility index cutoff of 40%. The diameter is self explanatory, though they don’t mention where on the IVC it was measured or how. The collapsibility index (CI) could be done from frozen images at end inspiration and expiration or from an M mode tracing. The rub with M mode is that the IVC moves up and down and side to side as the patient breathes but your M mode line doesn’t, so you’re sampling different parts of the vein. Essentially, you just subtract the diameter at end inspiration (when it is smallest in caliber) from the diameter at end expiration (max plumpness). That number is your numerator and the diameter at end expiration is your denominator giving you the percentage collapse with breathing. So, if your max diameter was 2 cm and your minimum diameter was 1 cm, your calculation would look like (2 -1) / 2 = 50%. If it only collapses to a diameter of 1.5 cm then you get (2 - 1.5) / 2 = 25%. That’s your CI. Below, the diameter is abbreviated IVCD and the CI as IVCCI.

By the time the volume status POCUS team was consulted all patients had already been treated for a while. Median time of POCUS was 72 hours from diagnosis of AKI. Prior to enrollment 43 had received an avg daily dose of albumin > or = 25 g and 10 had received at least 500 mL normal saline per day. Diuretics had been withdrawn in all. Median serum creatinine was 3.2 and MELD was 29. Here’s a summary of the treatments recommended based on the POCUS findings:

Fluid depleted - continue 1 g/kg/d albumin (max 100 g/day)

IAH (Intra-abdominal hypertension) - large volume paracentesis

Fluid repleted - match I’s and O’s, treat HRS with vasoconstrictors

Fluid expanded (overloaded) - give furosemide 80-160 mg q8-12 h

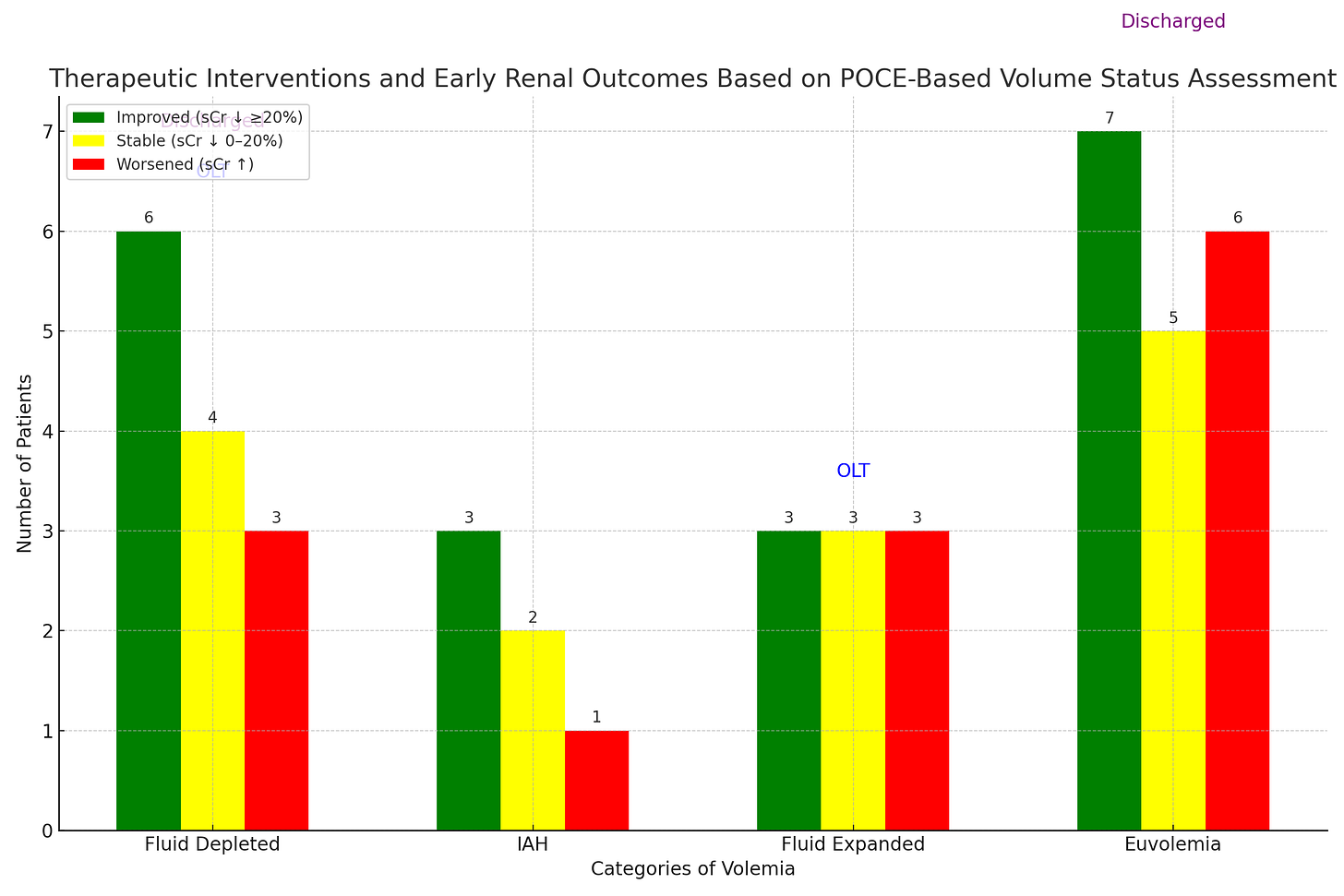

Among 53 included patients, they reclassified 15 as depleted, 8 as having intra-abdominal hypertension, 11 as expanded (overloaded), and 19 as euvolemic. The treating team followed recommendations in 32 of 34 from the re-classified groups and here’s how it shook out:

Ignore the ‘OLT’ floating above ‘fluid expanded’ - I used Chat GPT to make the bar graph from a table in the article and it decided to huck that in there. 2 patients in the fluid depleted cohort, 1 patient in the fluid expanded cohort, and 1 patient in the euvolemic cohort aren’t included above because they either got a new liver, left within 24 hours, or went on hospice/end of life care.

Their primary outcome, which is of dubious clinical significance, was a reduction in serum creatinine of >20% within 48-72 hours of initiation of therapeutic based on reclassification. So…essentially, did the creatinine look a lil better after the team did what they told them to do? As you can see, more patients got better or stayed the same (based on that outcome) than got worse. LOTS of caveats. No control group, selection bias (patients evaluated on request), POCUS evals happened over a pretty wide range of times from admission/diagnosis with AKI, accurate I/O data was not available (smells like real life), confirmation of IAH via bladder pressure wasn’t routinely available or reported, concomitant use of midodrine/octreotide happened in about 25% of the cohort, therapeutic interventions weren’t controlled or uniform and were implemented with a delay, and I already mentioned that the outcome was kind of arbitrary. There was no reported long term follow up and no mention of how many patients ultimately fully recovered. BUT. This is still way better than the way we usually do it, which is load people up with lots of albumin and then beg on our knees with prayer hands clasped for nephrology or GI to give the okay for terlipressin (it’s restricted at my hospital). And sometimes we induce iatrogenic respiratory failure from the 30 car pile-up of fluid in their lungs when we give them 200 g of albumin they never needed. I think this (combined with VExUS maybe?) will be how I approach these patients in the future and would love to implement a similar, albeit more standardized, decision tree at our institution some day.