What is VTI?

Velocity-Time Integral: A Bedside Echocardiography Technique Finding a Place in the Emergency Department

This article was e-published in the Journal of Emergency Medicine October 9

PMID: 36224055

VTI - what is it? I don’t know, I don’t know…

I do know, though, so lemme tell ya.

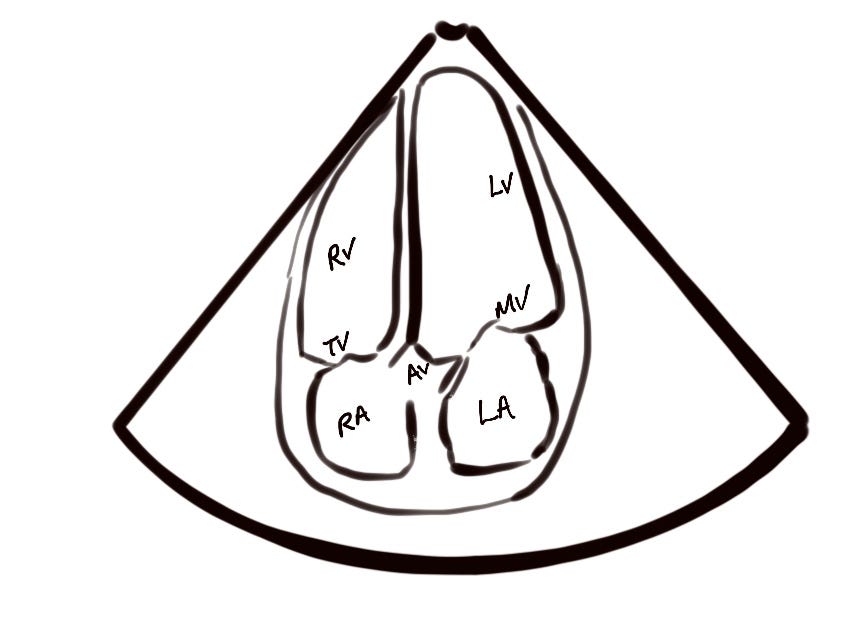

Velocity Time Integral is a measure used to calculate stroke volume. It is acquired with pulse wave Doppler (PWD) in an apical 5-chamber view of the heart.

The Doppler gate is aligned parallel to the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) about 5 mm from the aortic valve (in the direction of the apex). The more parallel to the direction of blood flow your gate is the more accurate your estimate will be.

If your machine has the ability to superimpose PWD on color Doppler you can place the gate in the bluest part of the LVOT jet.

When you’re lined up and you start the PWD you should see negative deflections graphed below the image. They’re negative because sound waves are bouncing off red cells moving away from the probe. The baseline is adjusted up to utilize as much screen as possible for the negative deflection and you select ‘calculate VTI’ or some such option.

Next you trace the deflection with your finger, baseline to baseline. The machine generates an area measurement of the shape you just traced and congratulations you did calculus! The integral is the area under the velocity over time (v/t) curve. Repeat for 3-5 deflections if there’s variability and record an average. Normal is between 17 and 23 cm2. Below that range ought to raise concern for cardiogenic, obstructive, or hypovolemic shock. Regardless, if they’re in the hospital for something heart related and the VTI is low that is no bueno. It is, in fact, muy mal. I’ve been watching the Spanish broadcasts of World Cup games on Peacock because it’s way cheaper than paying for TV for a month. Queremos cerveza! Above that range might indicate distributive shock, high output HF, or other myriad conditions generating high cardiac output (CO). VTI is a useful proxy for CO because it is directly proportional to it.

Stroke Volume (SV) = VTI x area of LVOT

CO = SV x HR

If you are just trying to assess ‘fluid responsiveness’ you can use the pre and post bolus VTI to make that call without subjecting your CO guesstimate to additional sources of error by trying to get the LVOT area just right. To further simplify things, the authors advise a passive leg raise, which mimics the effect of a 300-500 mL bolus of fluid except it’s rapidly reversible. So grab a VTI pre leg raise and look for a 15% increase post leg raise. If it goes up by 15% the patient is ‘fluid responsive’, if not consider early pressors.

The authors write that the VTI is easy to perform and reproducible. In my experience it’s easy enough for someone who is comfortable with cardiac ultrasound but tough if you’re still getting your bearings or have a hard time with the apical 5-chamber view. They note that it takes them between 2 and 4 minutes to perform. Add a few minutes to that to account for appropriate patient positioning and machine setup, gel application and cleanup, and finding the right buttons to push. And practice! In addition to patients you bolus practice on stable hospitalized patients admitted for non cardiac stuff and see if your day-to-day measurements match up. Perfect practice makes perfect - always do it like it matters and when it matters you’ll do it well.